MOTIVATION

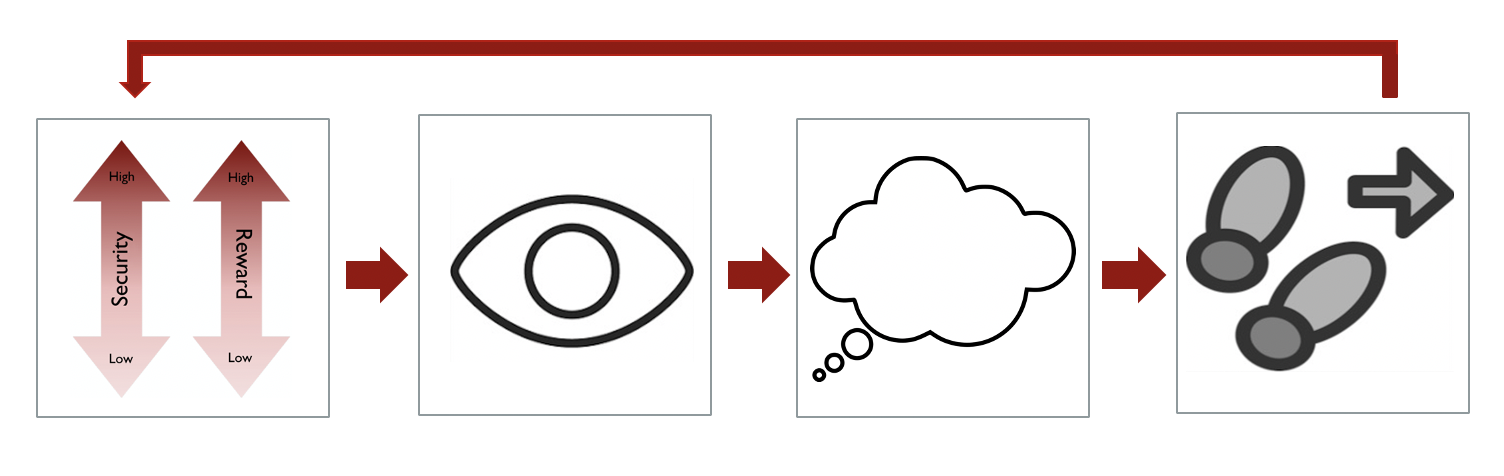

When we are in distressed moments, our fears, our losses, and our desires or difficulty obtaining them become very salient. The overwhelming impact and burden of stressful events make us aware of how much we feel driven to make everyday decisions by simultaneously weighing how much threat we are faced with versus how much opportunity we are missing out on for ourselves or for our families. However, even in calmer times, nearly every decision we make in our daily life reflects a balance of threat and reward.

When we are in distressed moments, our fears, our losses, and our desires or difficulty obtaining them become very salient. The overwhelming impact and burden of stressful events make us aware of how much we feel driven to make everyday decisions by simultaneously weighing how much threat we are faced with versus how much opportunity we are missing out on for ourselves or for our families. However, even in calmer times, nearly every decision we make in our daily life reflects a balance of threat and reward.

ATTENTION

To effectively manage these emotional moments, we focus our attention and rely on our senses to receive information about a situation to assess how much personally relevant and rewarding opportunities are present but also, how much risk and effort stands in our way. All the while, our brain is working like a calculator to help us weigh the possible benefits and rewards in the face of risk and effort so that we choose the best course of action to take in that moment. But, particularly in these times of distress, these feelings and urges can feel especially intense and confusing, which can constrain our attention and make us not want to stay in contact with difficult feelings and images, undermining our ability to know what actions to take.

To effectively manage these emotional moments, we focus our attention and rely on our senses to receive information about a situation to assess how much personally relevant and rewarding opportunities are present but also, how much risk and effort stands in our way. All the while, our brain is working like a calculator to help us weigh the possible benefits and rewards in the face of risk and effort so that we choose the best course of action to take in that moment. But, particularly in these times of distress, these feelings and urges can feel especially intense and confusing, which can constrain our attention and make us not want to stay in contact with difficult feelings and images, undermining our ability to know what actions to take.

METACOGNITION

In addition, there are times when the information about a particular situation is not available or is possibly contradictory or ambiguous. When environmental cues for threat and reward are subtle or ambiguous or when we are otherwise inattentive or distracted, our minds naturally “fill in the blanks” allowing us to remember how we handled past situations or imagining ourselves into future situations, to help us determine the best course of action in a given moment. But, distressing moments, especially during challenging experiences, can increase negative self-talk including worry, rumination, and self-criticism. These thoughts often revolve around seeing ourselves stuck, held back, or obligated to confront possible future threats or losses instead of focusing on what might be more personally relevant like our work or school, our family and relationships, or our community.

In addition, there are times when the information about a particular situation is not available or is possibly contradictory or ambiguous. When environmental cues for threat and reward are subtle or ambiguous or when we are otherwise inattentive or distracted, our minds naturally “fill in the blanks” allowing us to remember how we handled past situations or imagining ourselves into future situations, to help us determine the best course of action in a given moment. But, distressing moments, especially during challenging experiences, can increase negative self-talk including worry, rumination, and self-criticism. These thoughts often revolve around seeing ourselves stuck, held back, or obligated to confront possible future threats or losses instead of focusing on what might be more personally relevant like our work or school, our family and relationships, or our community.

BEHAVIORAL CONSEQUENCES

Finally, when our minds are filled with these distressing thoughts, cues of threat and loss may be amplified and overshadow our ability to notice the availability of pleasurable or rewarding opportunities or diminish our confidence in our ability to obtain them, or both. We are more easily triggered by something that reminds us of our distress. We look for ways to gain a greater sense of control, or to reduce a sense of threat, danger, or loss in hopes of pushing away, or reducing the intensity of the emotional experience. We are more likely to eat poorly, drink or smoke more, avoid things that take energy, or seek reassurance about ourselves from confidants or loved ones. Eventually, self-care becomes more difficult.

Finally, when our minds are filled with these distressing thoughts, cues of threat and loss may be amplified and overshadow our ability to notice the availability of pleasurable or rewarding opportunities or diminish our confidence in our ability to obtain them, or both. We are more easily triggered by something that reminds us of our distress. We look for ways to gain a greater sense of control, or to reduce a sense of threat, danger, or loss in hopes of pushing away, or reducing the intensity of the emotional experience. We are more likely to eat poorly, drink or smoke more, avoid things that take energy, or seek reassurance about ourselves from confidants or loved ones. Eventually, self-care becomes more difficult.